Spoiler alert: 162 million!

That’s right, as of August 1st, there are 330 active open-source projects hosted at the Eclipse Foundation and if you look across the 1120 Git repositories that this represents, you will find over 162 million physical source lines of code. But beyond this number, let’s look at how it was obtained, and what it really means.

That’s right, as of August 1st, there are 330 active open-source projects hosted at the Eclipse Foundation and if you look across the 1120 Git repositories that this represents, you will find over 162 million physical source lines of code. But beyond this number, let’s look at how it was obtained, and what it really means.

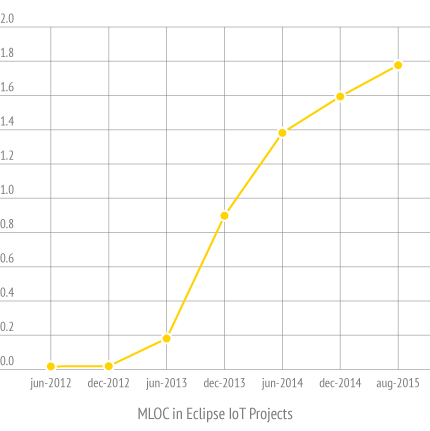

I’ve blogged several times about the importance of using metrics to monitor the health (and hopefully, growth!) of an open source project/community, and lines of code are just one. You should always have other metrics on your radar like the number of contributors, diversity, etc.

There are many ways, and many tools available out there, to count source lines of code. Openhub (previously known as ohloh) used to be a really good tool, but it doesn’t seem to be actively maintained. For a few years now, I’ve been relying on a home-made script to analyze Eclipse IoT projects, and it’s only recently that I realized I should probably run it against the entire eclipse.org codebase!

In this blog post, I will briefly talk about how the aforementioned script works, why you should make sure to take these metrics with a pinch of salt and finally, go through some noteworthy findings.

Line counting process

The script used to count the number of lines of code is available on Github. It takes a list of Eclipse projects’ identifiers (e.g ‘iot.paho’) and a given time range as an input and outputs a consolidated CSV file.

The main script (main.js) uses the Eclipse Project Management Infrastructure (PMI) API to retrieve the list of Git repositories for the requested projects and then proceeds to clone the repos and run the cloc command-line tool against each repo. The script also allows computing the statistics for a given time period, in which case it looks at the state of each repository at the beginning of each month for that period.

Once the main script has completed (and it can obviously take quite some time), thecsv-concat.js script can be used to consolidate all the produced metric files into one single CSV file that will contain the detailed breakout of lines of code per project and per programming language, the affiliation of the project to a particular top-level projects, the number of blanks or comment lines, etc.. It is pretty easy to then feed this CSV into Excel or Google Spreadsheets, and use it as the source for building pivot tables for specific breakouts.

Caveats

Just like virtually any KPI, you want to take the number of lines of code in your project with a grain of salt. Here are a few things to keep in mind:

All lines of code are not created equal

There is an incredible diversity of projects at Eclipse, and while a majority is using Java as their main programming language, there’s also a lot of C, C++, Python, Javascript, … 10M lines of Java code probably don’t carry the same value (i.e. how much effort has been needed to produce them) as 10M lines of C code.

Trends are more important than snapshots

It is nice to know that as of today there are 162 million lines of code in the Eclipse repositories, but it is, in my opinion, more important to look at trends over time. Is a particular programming language becoming more popular? Are all the top-level projects equally active?

I didn’t have a chance to run the scripts for a longer time period yet, but I will make sure to share the results when I get a chance!

Generated code, should it count?

There is a fair amount of generated code in some projects (in the Modeling top-level project in particular, of course), which certainly accounts for a few million lines of code. However, generated code often is customized, so I think it doesn’t necessarily skew the numbers as much as one would think.

Development does not always happen in a single branch

My script just looks at the code stored in the main (HEAD) branch of the Git repository. Some projects may have more than one development stream and may e.g. have a “develop” branch that is ahead of the main stable branch. Therefore, there is very likely more code in our repositories than what this quick analysis shows.

Additional findings

As my script outputs pretty detailed statistics, it is interesting to have a quick look at e.g. how the different top-level projects and programming languages compare.

Top 3 top-level projects: Runtime, Technology & Modeling

[table id=1 datatables_locale=”en_US” /]

Top programming language: Java

[table id=2 datatables_locale=”en_US” /]

If you end up using my script and have any question, please let me know in the comments or directly on Github!